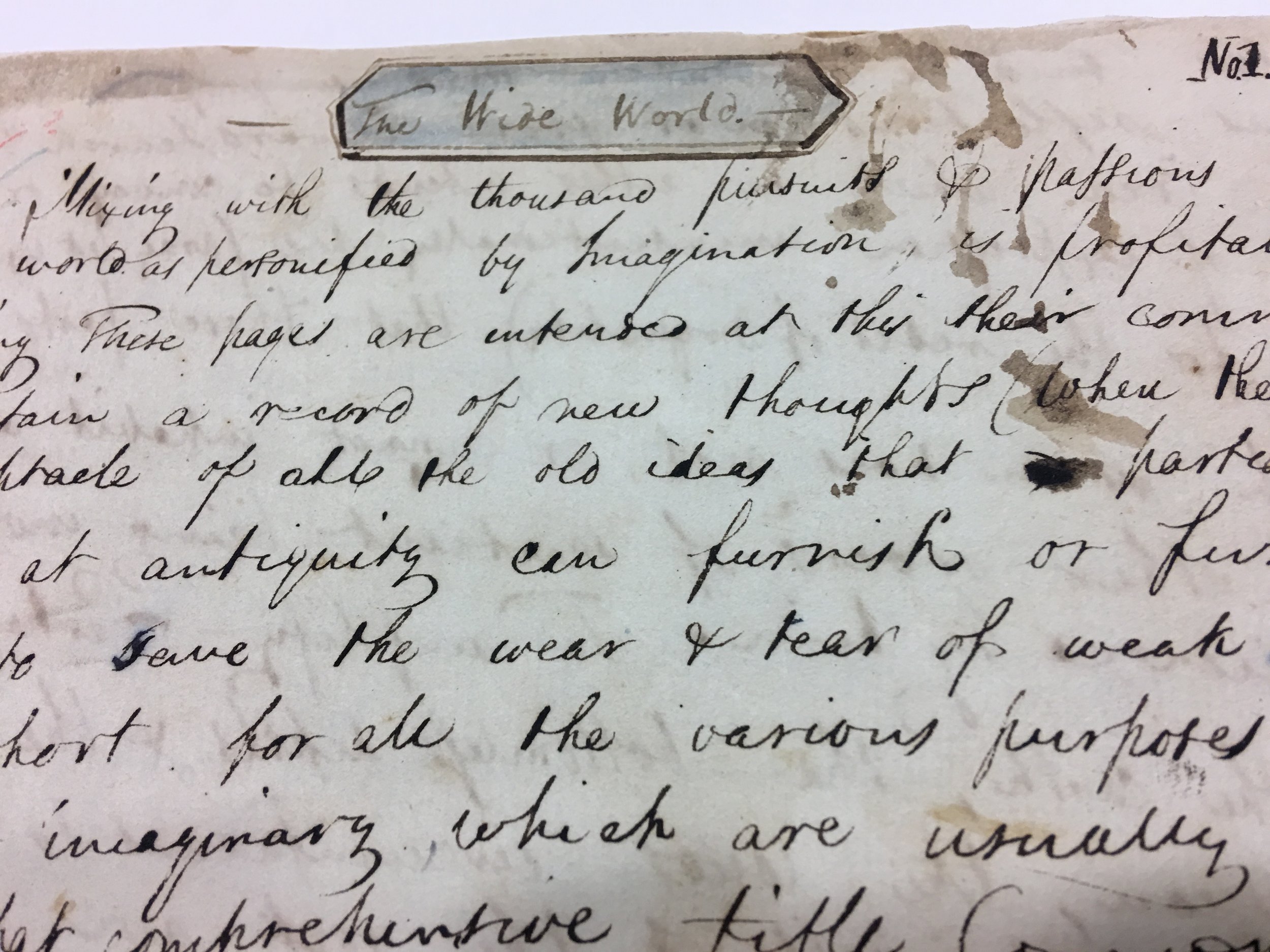

The Wide World

A pastel of Lidian by Jessie Noa. The bust of Emerson was created by sculptor Daniel Chester French. Photo by B. Ewen.

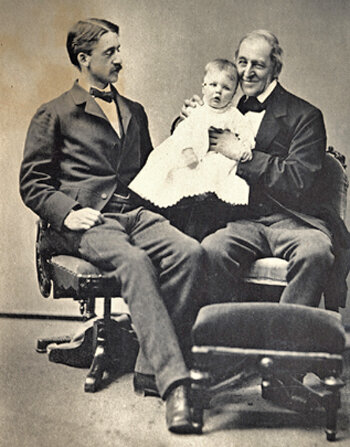

Lidian Jackson Emerson with her son Edward.

Lidian’s desk, built for her in Plymouth and brought to Concord in 1835. The heart shaped item was her pen wipe and it is resting on her lap desk. Photo by B. Ewen.

Lidian Jackson Emerson

We continue our Series on the Strong Women in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s life by profiling his wife Lidian (Lydia) Jackson Emerson.

Lydia Jackson was Ralph Waldo Emerson’s second wife and the mother to his four children. She fiercely opposed any cruelty inflicted on animals or people, and she stood up for those beliefs publicly at a time when women’s roles were often delegated to tending the home and raising the children. Horrified by slavery, she was a co-founder of the Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1837, and she was an associate member of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals at its founding in 1868, remaining its vice president her entire life. She was also a strong supporter of women’s rights.

Born in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1802, Lydia lost both her parents when she was sixteen-years-old. She experienced a religious conversion in 1825, and her Unitarian faith was very important to her for the rest of her life. By the time she met Emerson in 1834, she was living at the Winslow House in Plymouth and leading an independent life. Emerson and Lidian married in 1835 and moved to Concord, living there for the rest of their lives. However, Lidian never lost her love for Plymouth and visited regularly.

Lydia adopted the name “Lidian” upon marriage to Emerson. She was a graceful woman, who loved to dance and had a beautiful gait and posture. A voracious reader and intellectual; she studied German; wrote poetry; and attended many lectures, including those given by Emerson, and Margaret Fuller’s Boston Conversations. Emerson wrote after being introduced to her, “when two good minds meet, both cultivated, and with such difference of learning as to excite each the other’s curiosity and such similarity as to understand each other’s allusions in the touch-and-go of conversation.” [1] Lidian believed that a “most perfect marriage would be one in which opposite temperaments would be united.” [2]

Lidian was a multi-talented woman. Her daughter Ellen wrote about her, “she had a very large and varied vocabulary, probably because of her perfect memory and her constant reading, and her deep and powerful feeling brought it out in quite fresh forms continually.” [3] Lidian was a very conscientious manager of the Emerson household, where she habitually hosted visitors, friends and strangers alike. Emerson also traveled frequently giving talks across America and Europe, and was gone for long stretches of time. He was often lapse in his correspondence home and not as affectionate as Lidian might have liked. Lidian bore all the responsibilities of managing the house, the accounts, the staff and raising the children in his absences. Ellen remarked, “Economy was natural to Mother. She wished everything to serve all the purpose it could. She was, as naturally, magnificent and generous.” [4]

Emerson’s stature as a great writer and speaker brought an almost constant stream of ministers, writers, and artists to their home. Lidian welcomed them and often joined in their conversations with visitors sometimes finding her thoughts more interesting than Emerson’s. Her sense of humor helped keep Emerson grounded. She called the years 1840-1845 “Transcendental Times,” and “reliably popped the balloon of her husband’s pretensions. ‘Save me from magnificent souls,’ she told him, ‘I like a small common-sized one.’” [5]

In 1837, shortly after her marriage to Emerson, Lidian invited Southern abolitionists’ Angelina and Sarah Grimke to Concord for tea and a meal at the Emerson home. After they left, Lidian pledged not to “turn away my attention from the abolition cause till I have found where there is not something for me personally to do and bear to forward it.” [6] As Emerson biographer Robert D. Richardson, Jr. wrote in Mind on Fire, “as the Grimke sisters got to Lidian, so she undoubtedly got to her husband.” [7] Lidian advocated at home for Emerson to speak out more publicly for abolition. In fact, two months after the Grimke sisters’ visit, Emerson delivered an address on slavery in a Concord church. And in 1837, Lidian joined Mary Merrick Brooks and others to found the Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society.

With a compelling urge to push Emerson into action on humanitarian crises in America, Lidian took up the cause of the Cherokee Indians who were being forced to leave their lands in Georgia. “Lidian urged her husband to speak out against this ‘outrage on humanity;’ to remain silent was to ‘share the disgrace and the blame of its perpetration.” [8] Ultimately, Emerson wrote a protest letter to President Martin Van Buren.

Lidian loved all animals and worked hard to protect them and to relieve suffering. After joining the MSPCA, she wrote articles for their periodical and distributed copies to friends and acquaintances. Her devotion extended to the many animals at the Emerson House, especially the large troop of rescued cats. When the Emersons started to keep chickens, she worried about confining them, because they were digging up her gardens. Henry David Thoreau, a close family friend, made the chickens little cowhide shoes so they could still walk around and not destroy the plants.

Lidian experienced many emotional trials in her life. Grief joined the loneliness and burdens in her husband’s absences. With diseases like tuberculosis and scarlet fever rampant in the 19th century, families often suffered deep losses of life. In her forty-six years of marriage to Emerson, Lidian lost her first-born child Waldo when he was five years old; her sister Lucy; five Emerson family members and her close friends Elizabeth Hoar and Henry David Thoreau. The Emerson house caught on fire in 1872, forcing them to move out for more than a year. She lost her husband in 1882. With these tragedies to face, Lidian’s faith and commitment to end suffering kept her strong for herself and her family.

After Emerson’s death, Lidian continued to live a vibrant life, with trips to Plymouth; excursions around Concord; attendance at Bronson Alcott’s School of Philosophy; and visits to her grandchildren in Milton and Naushon. At the age of eighty-seven years, she found a Boston shopping trip with her daughter Ellen exhilarating. She lived with Ellen until 1892 when she passed away at the family home.

Lidian’s life was very well lived.

[1] Robert D. Richardson, The Mind on Fire, (Berkley, California: University of California Press, 1995), 191.

[2] Qtd in Richardson, 192.

[3] Ellen Tucker Emerson, The Life of Lidian Jackson Emerson, (East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 1992), 121.

[4] Qtd in Ellen Tucker Emerson, 96.

[5] James Marcus, Glad to the Brink of Fear, (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2024), 108.

[6] Qtd in Richardson, 270.

[7] Qtd in Richardson, 270.

[8] Ralph L. Rusk, The Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson, (New York, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1949), 523.

B. Ewen, Ralph Waldo Emerson House

MARY MOODY EMERSON.

PHOTO BY B. EWEN

COURTESY OF CONCORD FREE PUBLIC LIBRARY

MARY’S ELM VALE FARM BORDERED BEAR POND IN WATERFORD MAINE.

MARY MOODY EMERSON IS BURIED IN SLEEPY HOLLOW CEMETERY IN THE EMERSON FAMILY PLOT. THE INSCRIPTION ON HER HEADSTONE WAS WRITTEN BY RALPH WALDO EMERSON. PHOTO BY B. EWEN.

The Strong Women in Emerson’s Life

This month we begin a Series profiling some of the strong women who were very much a part of Emerson’s life, starting in his childhood. We start with his Aunt Mary Moody, who was instrumental in shaping Emerson’s ideas, writing and actions, starting after his father died when Emerson was just eight-years-old.

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Aunt Mary Moody Emerson delivered “the most important part of Emerson’s education,” ultimately influencing his views, reading habits, and his writing. [1] Waldo [2] wrote “A good aunt is more to the young poet than a patron.” [3]

Her involvement in Waldo’s life commenced after his father William Emerson died in 1811 and Mary stepped in to help his widow Ruth raise her five sons. While Mary changed her living situation frequently, her influence was provided through thousands of letters and copies of her journal Almanack, started when she was 20 years old. Waldo began his own journal, The Wide World when he was 17 years old and a student at Harvard. She counseled all the Emerson boys to do what they were afraid to do.

Mary’s Almanacks and letters became a rich source of material for Waldo in his own writing, his poems, essays, and lectures. He kept four MME workbooks and often pleaded with Mary to send him sections of her Almanack, which he routinely copied and referred to as his career progressed from minister to author and speaker. After rereading Mary’s letters in 1841, he wrote, “Aunt Mary…is a genius always new, subtle, frolicsome, judicial, unpredictable.” [4]

Mary Moody Emerson was born in 1774 to William and Phebe Bliss Emerson; one of their five children, who also included Waldo’s father. Shortly after the American Revolution commenced beside the family home – Concord’s Old Manse – and with her father going to war as a military chaplain, two-year old Mary was sent to her grandmother in Malden, Massachusetts. (This was not an uncommon practice to share responsibility for children among family members).

Mary’s father, William, died in 1776 and even after her mother, Phebe, remarried Mary was not called back home. She often referred to this period as her “infant exile.” [5] Her grandmother also died when Mary was four years old and she was adopted by her Aunt Ruth Emerson. Mary’s childhood was characterized by drudgery and a lack of money and food.

Despite humble beginnings and very little access to formal education, Mary became a prolific (but largely unpublished) writer and a voracious reader of works by such authors as Milton, Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Plato, and Boston minister William Ellery Channing. She directed her nephew Waldo to read and appreciate these writers.

Mary decided at an early age not to marry (although she was asked). Fiercely independent, by the 1830s Mary championed causes of those oppressed, including antislavery movements and women’s rights to better education. She supported her nephew Charles as he gave an antislavery address in Concord in 1835, and attended several abolitionist gatherings. She counted intellectual and free-thinking women as her friends and confidantes, including educator Elizabeth Peabody, scholar Elizabeth Hoar, abolitionist Mary Merrick Brooks, scientist and educator Sarah Alden Bradford Ripley, and Waldo’s wife Lidian Emerson. Mary introduced Lidian to Mary Merrick Brooks, prompting Lidian to join Concord’s Female Antislavery Society.

Mary’s appreciation for nature and its impact on thought occurred much earlier than the mid-nineteenth century reflections that permeated essays, books, and talks written by Waldo, Thoreau and others. In the early 1800s, in the words of her biographer, “she lived and wrote a celebration of the solitary imagination and of nature as analogous to God, valuing both explicitly as a woman’s resources.” [6] In 1831, Mary purchased a farm in Waterford, Maine, which she named Elm Vale. She often wrote to her nephews to share her appreciation for the landscape surrounding Elm Vale, including the mountains, the trees and Bear Pond. Waldo, Ruth (Waldo’s mother), Charles and Lidian Emerson, Elizabeth Hoar, Sarah Alden Bradford Ripley, and Elizabeth Peabody, all visited Mary at “Elm Vale”. Mary sold Elm Vale in 1851, which was necessary but also very difficult for her. Before she left she wrote in her Almanack, “What a bird dancing on that graceful limb. Had I but his iron pen how could I give praise for every bird & tree w’h have met my responding senses in this tranquil and beautiful vale.” [7]

Energetic and very outspoken, Mary was often considered difficult and challenging. But those challenges were more than compensated with her commitment and support to the contemporaries and young people she valued. After meeting with Mary when she was 77 years old, Henry David Thoreau wrote, “it is perhaps her greatest praise and peculiarity that she, more surely than any other woman, gives her companion occasion to utter his best thought. In spite of her own biases, she can entertain a large thought with hospitality…In short, she is a genius…” [8]

Robert Richardson, Jr., author of the Emerson biography The Mind on Fire, wrote in praise of Phyllis Cole’s Mary Moody Emerson and the Origins of Transcendentalism, “Mary Moody Emerson was a founder of Transcendentalism, the earliest and best teacher of R. W. Emerson and a spirited and original genius in her own right.” [9]

Mary Moody Emerson died on May 1, 1863, at the age of 88. Six years later, on March 1, 1869 Waldo delivered an address entitled Amita (Latin for Aunt) to the New England Women’s Club in Boston. More than 100 people attended – including Lidian and Ellen Emerson, Elizabeth Peabody, Julia Ward Howe and Louisa May Alcott. In his talk he said that Mary “gave high counsels. It was the privilege of certain boys to have this immeasurably high standard to their childhood; a blessing which nothing else in education could supply.” The minutes recorded from the event pointed out that the presentation enabled attendees to consider “a New England woman of rare gifts and originality of character.” [10]

[1] Robert D. Richardson Jr., Mind on Fire. (Berkley, California: University of California Press, 1995). 23.

[2] While at Harvard, Emerson decided that he wanted to be addressed as “Waldo” not “Ralph.”

[3] Qtd in Evelyn Barish, Emerson. The Roots of Prophecy. )Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1989). 53.

[4] Qtd in Richardson, 25.

[5] Qtd in Phyllis Cole, Mary Moody Emerson and the Origins of Transcendentalism. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998). 71.

[6] Qtd in Cole, 8

[7] Qtd in Cole, 279.

[8] Qtd in Cole, 283.

[9] Robert D. Richardson Jr., Book jacket blurb, back cover of Phyllis Cole’s Mary Moody Emerson and the Origins of Transcendentalism. Paperback and hardcover editions.

B. Ewen, Ralph Waldo Emerson House

ROCKING HORSE DIAMOND IN HIS PLACE TODAY IN THE EMERSON NURSERY. PHOTO BY B. EWEN

THE PLAQUE THAT PROVIDES DIAMOND’S NOTABLE DATES AT THE BASE OF THE ROCKING HORSE. PHOTO BY B. A. ECONOMOU

AN EXTERIOR VIEW OF THE EMERSON HOUSE FROM AN ENGRAVING BY JOHN B. FOREST, AFTER AN IMAGE BY THE HUDSON RIVER SCHOOL PAINTER WILLIAM RICKARBY MILLER, WHICH APPEARED IN A BOOK TITLED HOMES OF AMERICAN AUTHORS (NEW YORK: G.P. PUTNAM, 1855). EDDY AND LIDIAN (AND DIAMOND, THE ROCKING HORSE) CAN BE SEEN IN THE FOREGROUND ON THE LEFT.

Diamond

In the nursery on the second floor of the Ralph Waldo Emerson House in Concord is a substantially-sized antique wooden rocking horse -- with a rounded base, leather saddle and ears, and a horse-hair mane and tail. It stands about three feet tall and four feet long. By Emerson family tradition, the horse's name is "Diamond." On the base, a carved inscription reads:

Built about 1750

Bought of Mrs. Sophia Parker

At Woods Hole 1825

By Lydia Jackson of Plymouth

Given to children of N. & C. Russell

And by them returned to her son

E. W. E. Concord 1849

Repaired 1885

For as long as I have been a regular visitor to the Emerson House, the rocking horse has always stood out as a fascinating object: full of character, a bit strange, nostalgic, suggestive of idyllic Victorian childhoods and lost Yankee-pastoral ways.

I've always been curious, too, about its history and provenance. The brief version of this history on the base answers some questions, but raises others. Lydia Jackson was Ralph Waldo Emerson's second wife, who hailed from Plymouth on the Massachusetts coast. "E.W.E." was Emerson's youngest son, Edward Waldo Emerson. But other details and persons are not as well known. I decided to try to chase down some of the history of the rocking horse. What I found was an entertaining and adorable story -- one that follows Diamond all over New England; touches on themes of childhood, illness, family, and domesticity; and involves two dramatic incidents at sea -- one of them a shipwreck.

In 1825, Lydia Jackson of Plymouth, Massachusetts went to stay with her maternal aunt, Sophia Cotton Parker, in Woods Hole, near Falmouth, on the southwestern coast of Cape Cod. It was a three-week trip, one that Lydia, later called Lidian, would for the rest of her life remember fondly -- and to which she would even attach great, if somewhat obscure, significance. Lydia was twenty-three years old at the time, an orphan from the age of sixteen: intellectual, eccentric, sickly, deeply interested in matters of religion and the spirit, and, although not widely considered a great beauty, striking in appearance, with dark brown hair and a complexion of "Cherries in milk," as one admiring female friend had it. She had not yet met Ralph Waldo Emerson, the minister-turned-lecturer-and-essayist who would later become her husband and companion of forty-seven years.

Ever since the nearly simultaneous death of both her parents in 1818, Lydia had boarded with various relatives in Plymouth, including, since 1821, her uncle Rossiter Cotton and aunt Priscilla Jackson Cotton. Her mother's sister Sofia Parker -- "Aunt Parker" as she was known -- lived 40 miles to the south in the seaside village of Woods Hole, where for years Sofia and her husband Seth Parker kept a local tavern. Seth Parker had died in 1814, and at the time of Lydia's visit to Woods Hole the widow Parker was seventy years old. Lydia counted her stay with Aunt Parker to be "one of the most important and interesting occasions of her life," as she later told her daughter Ellen, although she could never quite pinpoint why. She spent much of her time alone, on the hill behind the house, thinking to herself and reading Walter Scott's novel The Betrothed. "I don't know how it was, it was different from any other experience," she told Ellen. "I felt all the time as if my Mother's spirit was very near me."

The death of her parents was only one of the two major hardships that had afflicted Lydia in recent years. The other was a bout of scarlet fever she contracted in 1821 at age nineteen, which nearly killed her and left her permanently riddled with digestive problems and other mysterious ailments, whether organic or psychosomatic. In the aftermath of her illness, Lydia had developed a strict, ascetic diet; slept four hours per night (in emulation of Napoleon, an improbable hero for a twenty-three-year old woman with reclusive tendencies); experimented with a variety of medical therapies, from hydrotherapy to mesmerism to homeopathy; and observed an exercise routine that included her dancing steps, jumping rope, and leaping over a wooden footstool. The solace she found at her aunt's home in Woods Hole was welcome respite from the privation and anxiety of Lydia's life since the death of her parents.

Still, she needed to keep up her exercises, and it was in this context that Lydia first encountered the rocking horse, already an antique in 1825. Its early history is obscure. The toy had once belonged to Aunt Parker's son John Parker, Lydia's older cousin, who had received it as a gift from family friends in Roxbury around 1800 when he was a boy. Nothing else is known of the rocking horse's earlier history, except for what we are told by the inscription on its base: that it was made around 1750. And so about fifty years of the horse's history are essentially a blank. Given that it came to Woods Hole from Roxbury, it seems reasonable to assume it was fashioned somewhere in Boston or its environs — although who knows? After the Parker children grew up, the horse seems to have stayed in the immediate family. When Lydia saw the rocking horse, according to Ellen's later account, she "took a notion that it would be good exercise for her to ride it every day--almost as good as riding a real horse." Lydia offered to trade a mahogany table she owned back in Plymouth for the horse. Aunt Parker agreed, and, according to Ellen, "the exchange was effected by sea."

If a grown woman buying a child's toy for her own use seems a little strange, Lydia probably had more than just her exercise regimen in mind. Lydia was at that time just warming up to what was evidently her new familial role, that of a spinster-aunt. John Parker remembered that she had bought the horse not for herself, but rather for her niece, Sophia Brown -- the eight-year-old daughter of Lydia's older sister, Lucy Jackson Brown. Lydia was a doting aunt to Sophia and her younger brother Frank, and would become even more involved in their care after Lucy's miscreant husband Charles Brown abandoned the family, running off to Istanbul, in 1834. Regardless of who was its intended recipient, though, the horse was soon bound by ship for Plymouth, and Lydia's cousin John, a sailor and a veteran of the naval war of 1812, agreed to accompany what had once been his own childhood toy on its journey thence.

At this point, the story of the rocking horse takes a picaresque turn. According to a later account by Ellen Emerson, John Parker reported that "some drunken sailors” aboard the ship “pushed it overboard." And what do you do with a drunken sailor? Ellen’s account goes on: "The Captain he scolded them & made 'em look for it, & they found it, only its head was broken off in the fall." After cousin John delivered the broken pieces of the rocking horse in Plymouth, presumably retrieving the mahogany table in the process, Lydia herself returned to Plymouth at the end of her three weeks in Woods Hole. Once home with her aunt and uncle Cotton, she was able to get the toy mended. And indeed if you examine the artifact closely today you can see a fracture line where the head was clearly broken off and reattached.

The details of the next twenty-five years or so of the rocking horse's history are somewhat sketchy, although the object seems to have remained in Plymouth. Sophia Brown presumably played with it as a toy in her childhood. Ultimately it was given -- or possibly sold -- to family friends. The inscription informs us that the horse was "given to children of N. & C. Russell," without specifying exactly when. "N. & C. Russell" were Nathaniel Russell, Jr. (1801-1875) -- the older brother of Lydia's best friend Mary Russell -- and Nathaniel's wife, Catherine Elliott Russell (1807-1884). Nathaniel and Catherine Russell's four children were Elliott (b. 1828), Martha (b. 1830), Francis (b. 1832), Anna (b. 1835), Nathaniel (b. 1837), and Kate (b. 1840). Some or all of these Russell children likely played with the rocking horse.

The larger Russell clan were among Lydia's closest connections in Plymouth. Mary Russell was her friend and confidante. Mary and Nathaniel's father, also named Nathaniel, was an iron manufacturer, local notable, and former ship's captain who in 1827 had purchased a fine Federal-style mansion in downtown Plymouth. "Captain Russell," as he was known, was an ebullient personality and a friend of Lydia's parents before their deaths. It was natural that the rocking horse should be left in the orbit of this prominent local family when, in 1834, Lydia departed Plymouth to begin her new married life with Ralph Waldo Emerson in Concord. In fact, it was inside the Russell home on Court Street that Lydia, by then aged 32, first met Emerson, at a social gathering after a lecture he had given in Plymouth in February 1834. A brief courtship and proposal followed. Depending on when the rocking horse was given to the Russell children, it may have been on the premises for Lydia and Waldo's first meeting. Alternatively, if the horse was still in Lydia's possession, it may have looked on during their wedding at Winslow House in Plymouth on September 14, 1835.

In any case, the toy did not follow the newlyweds when they moved to Concord into the house they would call "Bush" (now the Ralph Waldo Emerson House). Waldo and Lydia -- who was now renamed "Lidian" at her husband's prompting -- lived in Concord for the next forty-seven years, as the couple hosted a constant stream of visitors in their home, Waldo became one of the preeminent figures in American literature, and Lidian gave birth to four children: Waldo (b. 1837), Ellen (b. 1839), Edith (b. 1841), and Edward (b. 1844). The rocking horse did not figure into the childhoods of the older Emerson children, although there are glimpses to suggest that other toy horses were present in the home. In July 1839, Emerson writes of Waldo in his journal: "I like my boy with his endless sweet soliloquies & iterations and his utter inability to conceive why I should not leave all my nonsense, business, & writing & come to tie up his toy horse, as if there was or could be any end to nature beyond his horse. And he is wiser than we when he threatens his whole threat 'I will not love you.'" Waldo died of scarlet fever in 1842, at age five -- an event that devastated both parents and inspired Emerson's poem "Threnody." Lidian's old rocking horse, meanwhile, gathered dust in the garret of the Russell house on Court Street.

Rocking horses do not appear again in the historical record of the Emerson household until early 1848 -- a time of great activity for Emerson and the world at large. Democratic revolutions against monarchical rule were exploding across Europe; the potato crop failed in Ireland, leading to the Great Famine and mass Irish emigration to America; Italian unification was heating up; and a women's right's convention formed at Seneca Falls, New York. Emerson was in the midst of an eight-month journey abroad to Great Britain and France, from November 1847 until June 1848. In the course of his trip, his second to Europe, Emerson lectured all over England and Scotland, renewed his friendship with Thomas Carlyle, observed a mass Chartist convention in London, and visited Paris in the recent aftermath of the February Revolution. It was an eventful and formative experience for him, which he wrote about extensively in his book English Traits (1856).

But a more domestic duty also weighed on Emerson as he toured Europe. Before he had left Concord for Europe, the family's youngest son Edward, then aged three, had asked his father to bring him back a "red London orange" (a blood orange? a child's fancy?) and a rocking horse. In January 1848, Emerson was lecturing his way through Yorkshire when he received a letter from his eight-year-old daughter Ellen encouraging his speedy return home and reminding him of his promises to "Eddy." The plea came in the form of a rhyming poem:

Father is absent, at England is he,

He went in a ship a few weeks ago.

His form we do not any one of us see

Except in our dreams, -- when we wake we say, No.

O father, come quickly, bring Edward the red

His red London orange, & rockinghorse too.

For he would not like to know that tis said.

That oranges are no more red than they're blue.

Emerson shared Ellen's poem with Elizabeth Ashurst Biggs, the daughter of a radical lawyer and abolitionist hosted him in Manchester (and later a novelist in her own right). He commented that Ellen's verses were "pretty good for a girl who is not yet nine."

Emerson followed through on his promise, although he did not buy the rocking horse until the summer. His miscellaneous notebook of expenses from July 1848 records transactions with three London merchants -- John Davison of Hatton Garden, Robert Henderson of Snow Hill, and Paul Leach of Holborn -- with the word "rockinghorse" written next to them; it is unclear what part each of these men had in the fashioning of the toy. Although Emerson's notes are fragmentary and ambiguous, the purchase was apparently made for 50 shillings. Nothing is known of this other, English rocking horse that was intended for Edward -- not even its name. (Nothing more at all is said of the red London orange.) Emerson arranged to have the horse -- along with two busts of the Egyptian goddess Isis that he had also purchased on his European travels -- sail back to America aboard the Ocean Monarch, an emigration barque bound for Boston, which departed Liverpool on the morning of August 24, 1848.

But Eddy's London rocking horse never made it. The Ocean Monarch's August voyage, as it happened, turned into one of the most notorious shipwrecks of the mid-nineteenth century. The ship, launched the previous year and built by the Canadian-American designer Donald McKay, of clipper ship fame, was the largest in the American merchant fleet at the time, measuring 177 feet. Eight hours into her journey out of Liverpool, a fire broke out in the stern of the ship, probably caused by steerage passengers who had been smoking and from whom the captain had earlier confiscated smoking pipes. Passengers panicked and began jumping overboard. The ship dropped anchor, and after an extensive rescue effort conducted by nearby ships who had spotted the blaze, the Ocean Monarch sank 14 fathoms to the bottom of the sea, taking 179 souls with her -- as well as Emerson's furniture bound for Concord: the two busts of Isis and Eddy's rocking horse.

We know about the demise of the London rocking horse from a letter by Waldo to his older brother William on October 19, 1848, near the end of his European sojourn, which explains what happened and also efficiently recounts what happened next. "Did I tell you that Eddy's rocking horse & my casts of Isis were lost in the Ocean Monarch?" he asks. "The bill of landing was bro't me by Joseph Lyman. Lidian & the boy received the news at Plymouth, & Nathaniel Russell, to whom Lidian had once sold an old family rocking horse, only junior to the Trojan Horse, magnificently explored his garret, & made it a present to Eddie. The horse arrived in Concord amidst uproarious acclamations of our youngest people." And so there you have the story of how Diamond came back into the family: upon receiving the disappointing news that her son's toy was at the bottom of the ocean, Lidian had gone to her old friends the Russells. Captain Russell had dug out the old antique -- "only junior to the Trojan horse" -- of her young adulthood, told Eddy it was now his, and had the horse shipped to Concord, where it arrived to shouts of joy from the other Emerson children, Ellen and Edith.

It was at this point, according to Ellen Emerson, that the horse was given the name Diamond. The horse remained a beloved object among the Emerson children; this much is evident from the attention Ellen and Edward devoted to gathering and preserving its history when they were both adults. In 1870, after relaying an aging John Parker's memories of the rocking horse's misadventures at sea with the drunken sailors, and its subsequent repair, Ellen wrote to Edward: "Preserve this archive of the horse, I'll have it mended again." And she did, in 1885, if the inscription on the base is to be believed.

A later chapter of Diamond's history is known to me only because of family lore. For I have a more than scholarly connection to this object and its previous owners. Ralph Waldo Emerson was my great-great-great grandfather. Lidian was my great-great-great grandmother. Edward Emerson, "Eddy," their youngest son -- later a doctor and writer in his own right -- was my great-great grandfather. Edward's only surviving son, Raymond Emerson, to whom the rocking horse was passed on after Edward, was my great-grandfather. Raymond and his wife Amelia kept the rocking horse in the front hall of their home in Concord; upon their deaths, the horse was given back to the Emerson House, where it remains today.

I remember the first time I saw Diamond, it was during a tour of the Emerson House sometime around 2013, when I was reading quite a bit of Emerson's writing, becoming acquainted with his life and legacy as I studied American cultural and intellectual history in graduate school, and attempting to reconnect with the Emerson branch of my family history. I brought two nephews of mine -- my sister's sons -- on a tour of the Emerson House, where I had never been before, and where we were greeted graciously at the door by a guide. The guide walked us through the house without realizing that we were all of us descendants. When we reached the nursery, she pointed out the rocking horse and claimed that descendants of Ralph Waldo Emerson were still permitted, to this day, to ride Diamond. I leaned over to my nephews and whispered, "want to hop on, boys?" They smiled and said nothing; the guide looked confused.

After my visit to the house, I asked my Dad if he remembered anything about Diamond. And indeed he had fond memories of "Dinah," as he misremembered the horse's name: romping over it with his siblings and older cousins, essentially manhandling the poor thing in the foyer of his grandparents home during the 1950s. It's lucky, in all that horseplay, that they didn't break off the head again!

Charlie Riggs, PhD,

Great-Great-Great Grandson of Ralph Waldo Emerson

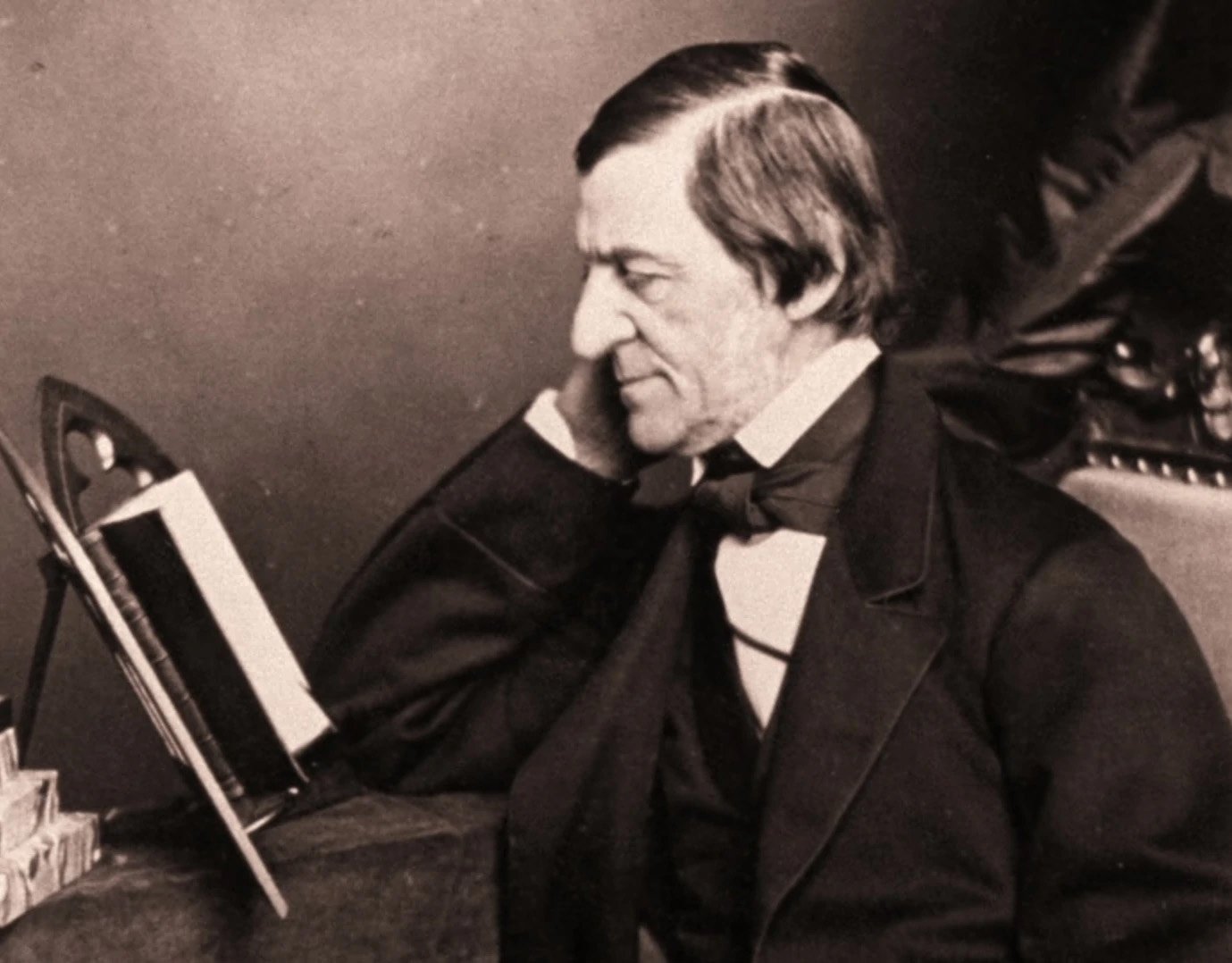

THE TRANSCENDENTALISTS OFTEN MET AROUND THE TABLE IN THE PARLOR. MARGARET FULLER SERVED AS THE FIRST EDITOR OF THEIR INNOVATIVE JOURNAL, “THE DIAL.“

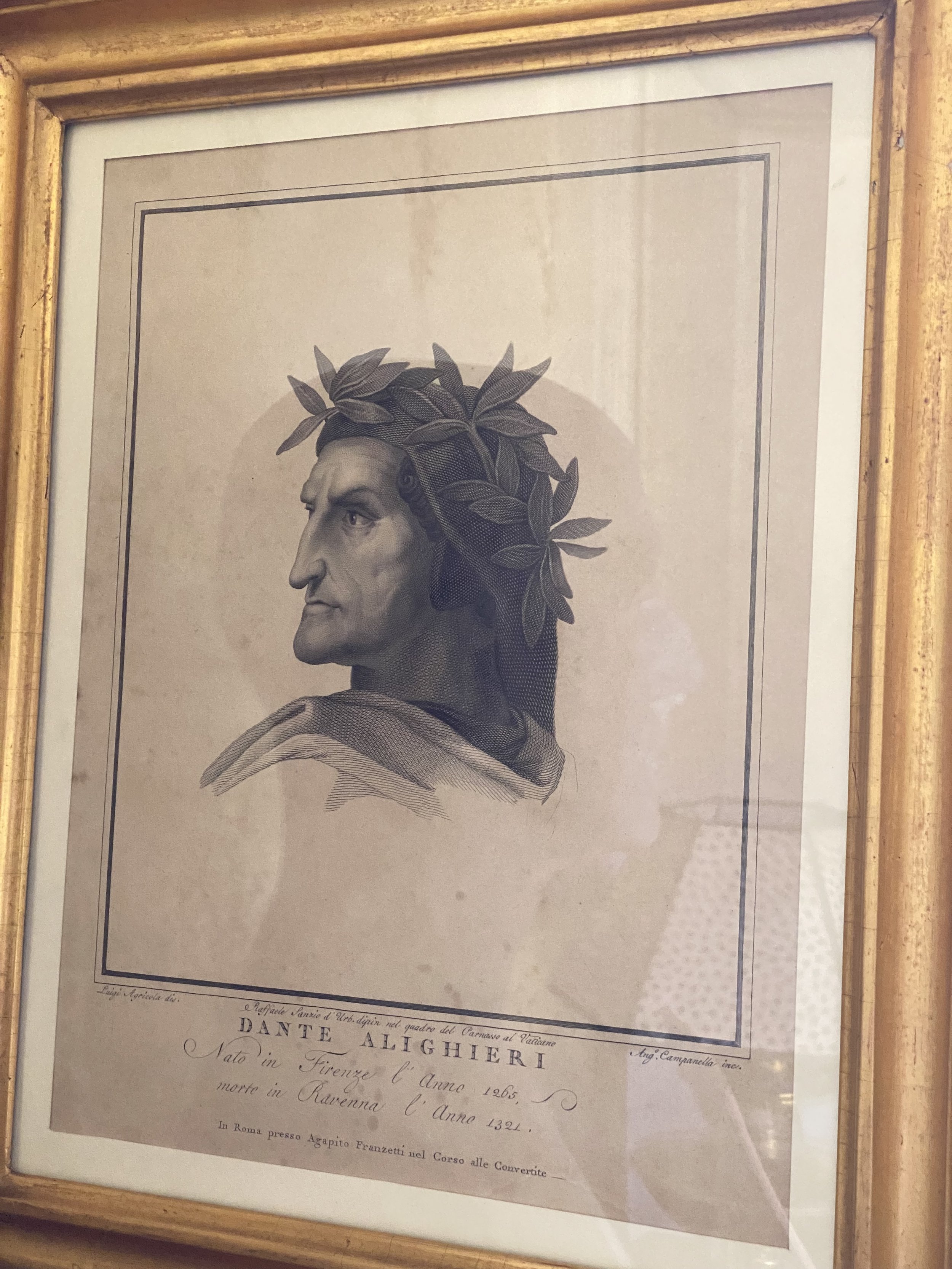

THIS PORTRAIT OF DANTE ALIGHIERI, THE GREAT 13TH-CENTURY ITALIAN POET, ADORNS THE NORTH WALL OF EMERSON’S STUDY.

“THE THREE FATES,” 19TH-CENTURY COPY AFTER SALVIATI. THE IMAGE HAS OCCUPIED PRIDE OF PLACE IN EMERSON’S STUDY SINCE 1845.

Frequently Asked Questions

We receive many questions from visitors to the Ralph Waldo Emerson house. Following is a sample of some of the frequently asked questions with our answers. Enjoy!

Why did Emerson choose to make his home in Concord after his marriage to Lydia Jackson?

His ancestral connection to Concord went all the way back to its beginning in 1635, as he was descended from one of the founders, Reverend Peter Bulkeley. His Grandfather William Emerson was at the North Bridge when “the shot heard round the world” was fired and eventually joined the Continental army as a chaplain. As a child, Emerson spent some time in Concord when life in Boston was too dangerous during the War of 1812. He moved to Concord and the Old Manse after his first wife died and he had traveled to Europe to figure out his life’s direction. His connections to the town were extensive.

He wanted to get away from the “compliances and imitations of city society.” Concord, with a population of around 2,000 – as compared to close to 100,000 in Boston – was very progressive with a lyceum by 1828, a library started in 1794, a strong antislavery society and a Mozart Society. By 1835, Concord had 66 college graduates and 6 school districts. And of course, Concord provided plenty of natural surroundings.

What were some of the topics of Emerson’s lectures?

Emerson’s range of content broadened as his career developed. He lectured on historical figures; aesthetics and the arts; the great causes of his day; important characteristics of humanity, such as duty, ethics, and self-reliance; and the connection between the mind and nature. His lectures were very well attended. For example, often his lectures in Boston had 300-400 attendees.

What did the Transcendental Club members talk about?

The Club was a forum for new ideas, frequented by Emerson, Bronson Alcott, Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Peabody, Sarah Alden Bradford Ripley, William Ellery Channing Elizabeth Hoar, a young Theodore Parker and other ministers including Frederick Henry Hedge, George Ripley, Orestes Brownson, Convers Francis and Chandler Robbins, who succeeded Emerson at the Second Church in Boston.

Typically, each meeting would center on a single topic such as “American Genius;” “Education of Humanity;” and “On the Character and Genius of Goethe.” Meetings were held in members’ homes, including Emerson’s. They produced a quarterly magazine entitled “The Dial.”

What languages did Emerson know?

Emerson studied Latin and Greek from an early age. Well versed in the classics, he also knew Italian, German, and French.

In 1843, Emerson completed a translation of Dante Alighieri’s Vita Nuova, The New Life, from Italian. In addition, Emerson translated hundreds of lines of Persian poetry—from German sources—to his native English.

What is the significance of the painting of three women over the mantle in Emerson's study?

Known as “The Three Fates,” the work is drawn from Greek myth and is usually considered an allegory of the human condition in which the Fates are personified by three sisters, the Moirae, who govern our destinies. The youngest, Clotho, spins the thread of life, the second, Lachesis, determines the length, and the oldest, named Atropo cuts it.

Emerson would have first encountered the original of Francesco Salviati’s 16th-century work at the Pitti Palace in Florence in 1833. Still grieving the untimely death of his first wife, Ellen Louisa Tucker, the image may have helped Emerson come to terms with the abiding loss. From another perspective, the painting may recall three women who nurtured and influenced him in youth: his mother, Ruth Haskins Emerson; his father’s sister, Mary Moody Emerson; and Sarah Alden Bradford Ripley, an aunt by marriage.

An early Hudson River School artist named William Wall, whom Emerson had met on that first trip abroad, knew he admired the Renaissance painting and had a copy made for him.

R. Davis, B. Ewen, Ralph Waldo Emerson House

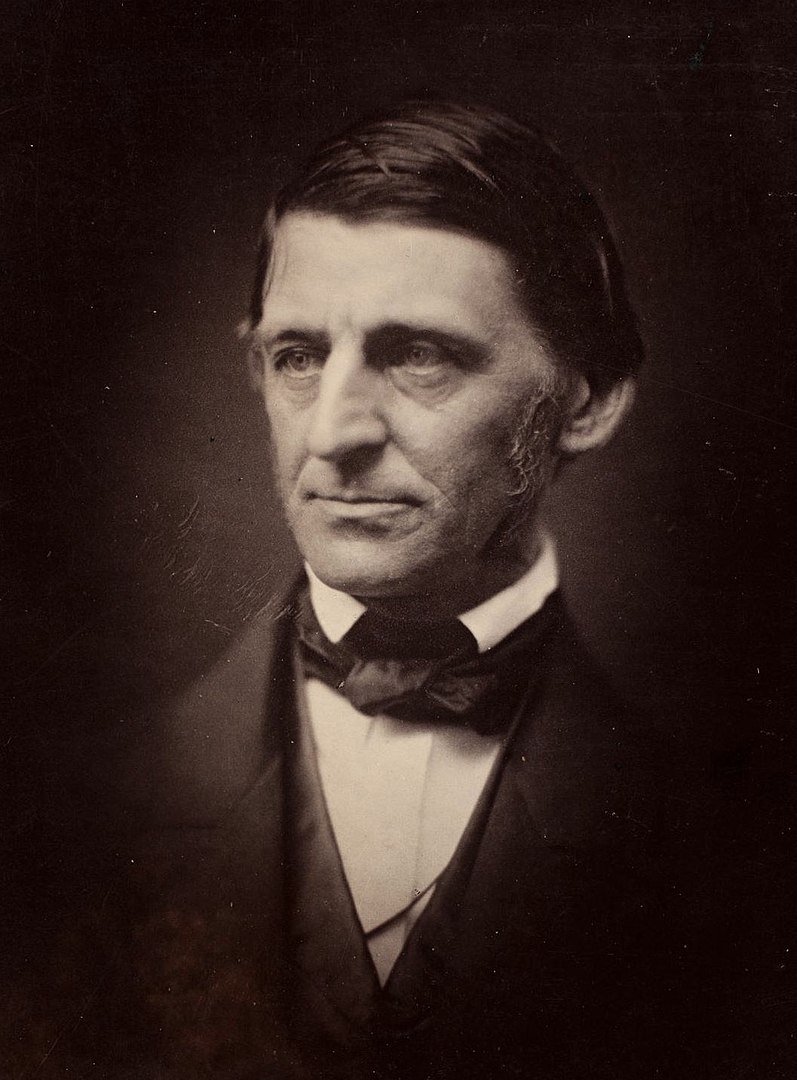

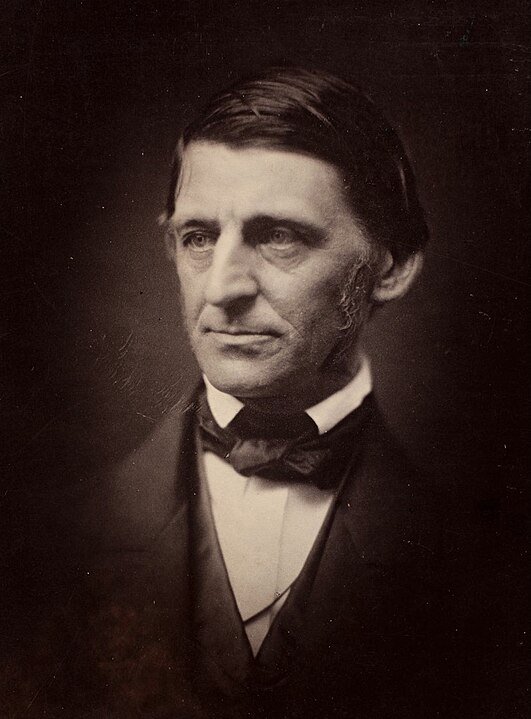

ralph waldo emerson

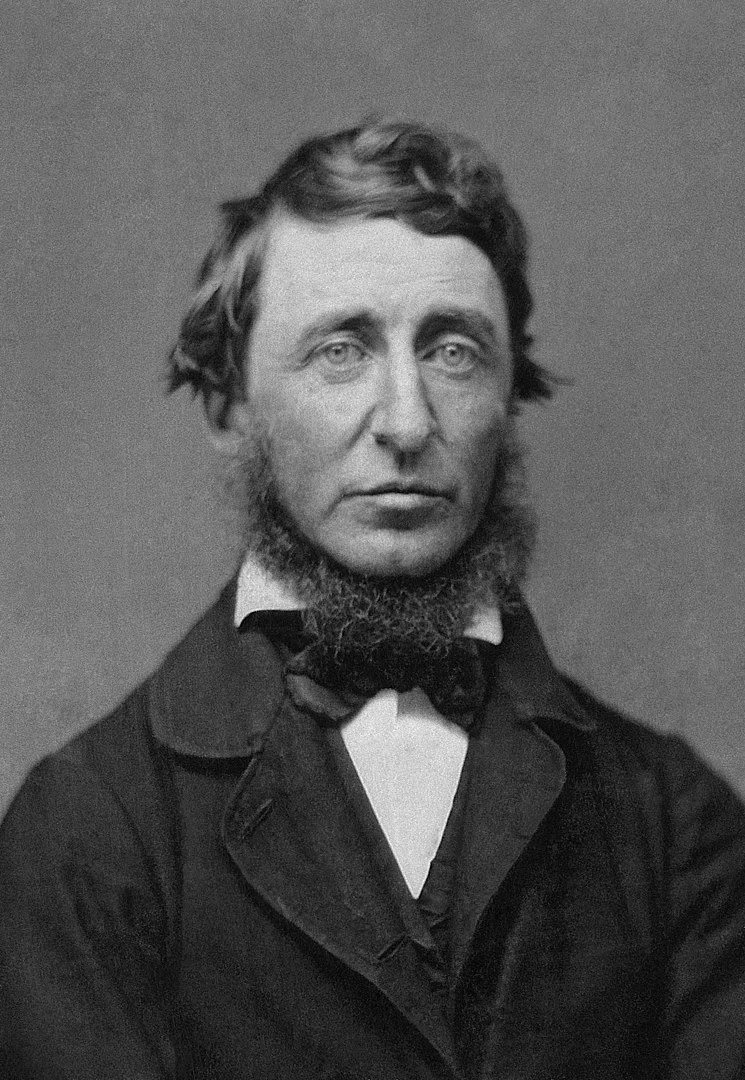

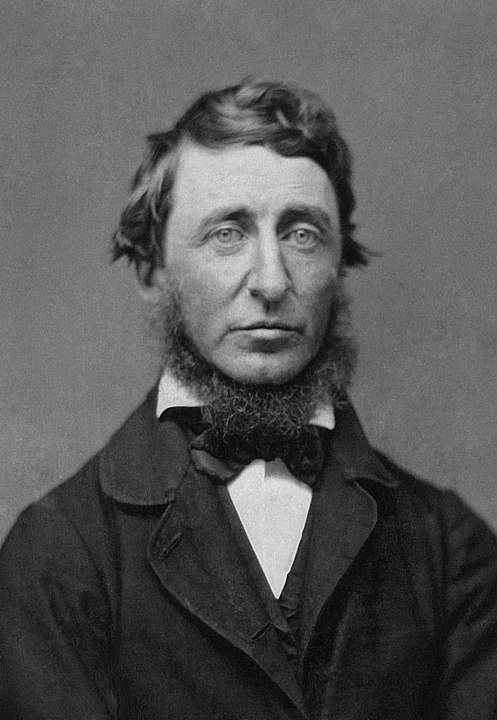

henry david thoreau

Whatever I May Call You

Visiting historic places can evoke a sense of history that we can not otherwise know. When we can occupy personal spaces, and experience how historical people inhabited these same rooms and landscapes, we can see aspects that inspired them, gain fresh perspectives, and make new connections. When a historic home, such as the Emerson House, retains the personal objects used by the people who lived there hundreds of years ago, a further contextualized layer is added to our experiences of the past anchored in place. The Emerson House collections bear many testaments to Henry David Thoreau’s close friendship with the family, and the times he resided together with them in their home. Other than his birthplace, where the Thoreau family resided briefly in his infancy, the Emerson House is currently the only home that Thoreau lived in that is open to the public as a museum. It was a place that he frequently visited, where he joined in conversation, made things with his hands, presented lectures, and partook in every day life.

Recently a visitor to the Emerson House was inspired to ask if Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Thoreau called one another “Waldo” and “Henry” when they were in a room together. To have been a fly on the wall! This is one thing that the house itself can’t tell us. Without time travel, we can never know the actual words spoken between the two men in a period on the cusp of sound recording, but personal documents – letters and journals – can offer us insight.

We found a somewhat surprising answer. In his book Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, Jeffery S. Cramer points to the first letter in which Thoreau addressed Emerson by his diminutive name, “Waldo.” Thoreau began, “For I think I have heard that that is your name” (qtd in Cramer 70). This letter was written in 1848, when Emerson was lecturing in Europe and Thoreau was in residence at the Emerson home, staying with Emerson’s wife, Lidian, and their children at Emerson’s request. This was nearly eleven years after the two men met in 1837; seven years after Thoreau had first come to live with the Emersons in 1841; six years after the friends had mourned together the double loss of Thoreau’s brother John and the Emersons’ eldest son Waldo in January 1842; and three years after Thoreau had moved into his house on Emerson’s Walden Pond wood lot. Letters were a more formal mode of communication, but, for many years, Thoreau had been fondly called “Henry” by Ralph Waldo and Lidian Emerson, and was known as “Uncle Henry” to their young children (38).

Previously, Thoreau had addressed his letters to Emerson, “My Dear Friend” (42, 69). This was perhaps owing to his deference to his elder and esteemed friend, who was fourteen years older than Thoreau. It was a term that carried deep affection, reflecting their familial relations and intimate kinship, for Thoreau continued, “Whatever I may call you, I know you better than I know your name” (70). Thoreau would often times, thereafter, refer to Waldo as “my friend,” (rather than by name) in his journal.

More than fifteen years after his friend’s death, Emerson, then seventy-five-years-old and suffering from aphasia, could no longer recall Henry Thoreau’s name. Although he had to call into the next room to ask Lidian to supply the words ‘Henry Thoreau,’ Emerson remembered his “best friend” no matter what he was called (102).

Works Cited:

Cramer, Jeffery S. Solid Season: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint, 2019.

K.L. Martin, PHD, Ralph Waldo Emerson House

Cranch himself, however, said the “blues” were simply part of his character, and always had been. For relief, he looked to music, and also to Emerson. Cranch could recite pages of Nature aloud; the book reliably lifted his spirits for four decades. Thirty-five years after the satirist and his subject went huckleberry picking together on Walden Pond, Cranch sent Emerson a new landscape painting to thank him for a lifetime of solace. “I owe you for all that your works have been to me.”

christopher cranch gave ralph waldo emerson this painting as a thank you. it resides in the dining room of the Emerson house.

Christopher Cranch, Transcendentalist, Artist and Follower of Emerson

The following article, written by Sasha Archibald, is reprinted from The Public Domain Review and captures the essence of Christopher Cranch, who turned some of Emerson’s essay phrases into illustrations, and became a devoted friend. We have one of Cranch’s paintings in the Ralph Waldo Emerson house, given to Emerson as a thank you “for a lifetime of solace.”

Public Domain Review Article

Christopher Pearse Cranch (1813–1892) is remembered for bringing levity to Transcendentalism. At the various gatherings that soldered the movement, the good-looking Cranch played the flute and guitar, loved to sing loudly, and pretended to talk to animals. “We have transcendental and aesthetic gatherings at a great rate”, he reported to his sister, “and they make me sing at them all. I have worn my Tyrolese yodlers almost to the bones . . . I am quite a singing lion.” Cranch was also quick with the pen, making witty sketches on the spot. His best party trick was to sketch satirical illustrations of sentences plucked from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Nature (1836) — a book that Cranch and his friends admiringly devoured. Emerson’s earthy, concrete analogies invited image-making.

It started one evening, when Cranch and a friend, the minister and publisher James Freeman Clarke, began illustrating various Emerson quotes by literalizing the author’s figurative language. The two men doodled and giggled, so much so that when the visit ended, they continued to exchange drawings in the mail. Cranch was the more skilled artist, and Clarke egged him on. Clarke collected some of the drawings into a scrapbook, titled Illustrations of the New Philosophy, and sent others round to friends — all people who revered Emerson and received the satire with its intended geniality. The sketches were passed among Transcendentalist-leaning social circles in New York and Boston to the point that Cranch bragged, “My drawings . . . permeate all houses, as water doth a sponge. Wherever I go I hear of them.” Clarke also sent a selection directly to Emerson, who received the caricatures not as an insult, but an overture of friendship. Emerson and Cranch soon became lifelong friends.

The sketches were cheeky, teasing, and toothless. They deflated Emersonian pretention, but were clearly the product of genuine delight — Cranch found Emerson’s language lively and fresh, and the drawings were his simpatico reply. One of the most popular depicted Emerson’s head perched atop a giant ridged melon, captioned with the Nature quotation, “I expand and live in the warm day, like corn and melons.” Others were similarly straightforward. When Emerson said in an address at Harvard, “Men in the world today are bugs”, Cranch drew a horde of upright insects, and when Emerson exclaimed “How they lash us with those tongues of theirs!” Cranch drew eight rope-like tongues and a cowering victim. Cranch’s illustration of “Few grown-up persons see the sun” is precisely what it says: a cluster of learned adults clueless to the radiance above. Even when the satire was more acerbic, it was a joke among friends. One such doodle, now lost, depicted Margaret Fuller driving the Transcendentalist carriage, reins in hand, with Emerson lounging in the back seat.

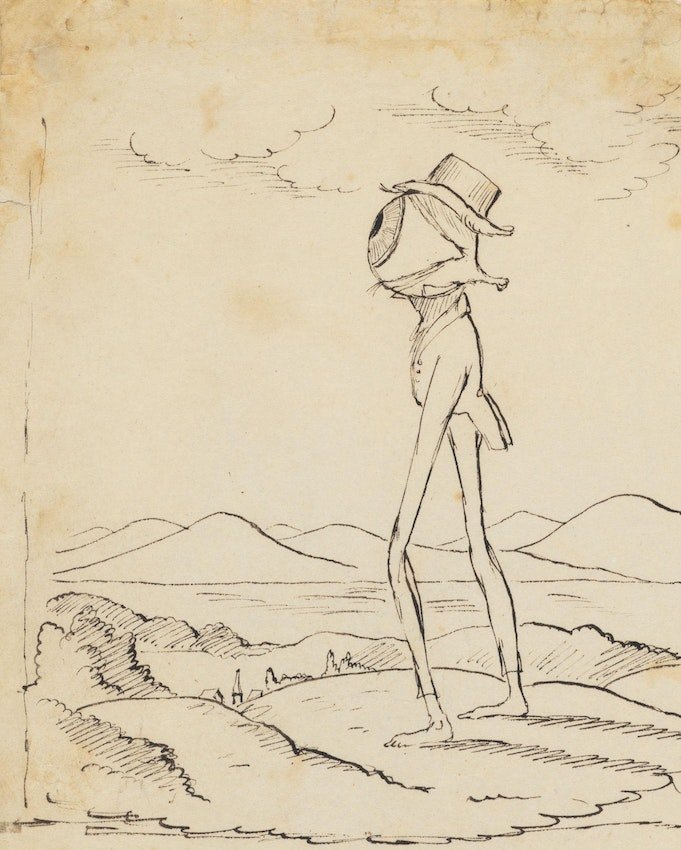

The best known of Cranch’s sketches is the “transparent eyeball” drawing. The version featured below shows an eyeball in a dinner jacket and top hat, his optic nerves forming a low ponytail. It was shrewd of Cranch to home in on this baffling phrase. Eyeballs perceive transparency, but aren’t themselves transparent, so what did Emerson mean? Context helps, a bit. “Transparent eyeball” appears near the end of Nature’s first chapter, when Emerson is trying to describe precisely why walking in the woods has a curative effect.

Standing on the bare ground,— my head bathed by the blithe air,— and uplifted into infinite space — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.

Bodily dissolution is key to these enchanted moments, except the body can’t entirely dissolve, because one part of the body — the eyes — induces the dissolution. “I am nothing; I see all” is the operational tangle that leads Emerson to the paradoxical “transparent eyeball”. Cranch’s illustrative figure is appropriately at odds with itself. Its posture is debonair, and its hands seem to have melted away, but its large eyeball-head, with barely the suggestion of a lid, stares upward, rapt and transfixed, as if communing directly with the sun.

Some scholars have described these jottings as the pinnacle of Cranch’s life achievement. That’s a little harsh, but it’s true that Cranch’s cleverness never begat an illustrious career. He came from a prestigious, accomplished family that was deeply intertwined over three generations with that of President John Adams and his son, President John Quincy Adams. (John Adams and Cranch’s grandfather married two remarkable sisters, Mary and Abigail Adams; Christopher Pearse Cranch married John Quincy Adam’s sister.)

Cranch was less conventional than his father, grandfather, and brother, and less impelled to do things he didn’t like doing. The poet and abolitionist James Russell Lowell described his friend thus: blessed with “gifts enough for three—only his foolish fairy left the brass out when she brought her gifts to his cradle.” As a young man, Cranch entered the ministry, but spoke with too much diffidence to be a charismatic preacher. He was never ordained, and instead traveled, taking the pulpit for short stints in different cities. His burgeoning interest in Transcendentalism threatened what thin career prospects he had, and after his dear friend and fellow Transcendentalist John Sullivan Dwight was forced to resign the ministry, Cranch quit in solidarity, and burned his sermons.

With no training of any sort, he announced at age thirty that he would become a landscape painter. Unfortunately, his talent was middling. A “major mediocrity” is how he’s described by his biographer. Cranch’s unorthodox career left his wife and family of three children perpetually short on funds. They couldn’t afford to live in New York — where “greenbacks melt like snowflakes on hot griddles”, Cranch complained in 1863 — and so they settled for a decade in Paris. Cranch painted a great deal, but he also translated Virgil, published poems and reviews in The Dial and other magazines, and wrote two novels for children. He corresponded with many distinguished friends, and penned opera star Jenny Lind’s adieu to her American audiences. But nothing stuck. Few of his paintings sold, and his four books of poetry landed too quietly. One of them, ill-advisedly titled Satan, reportedly sold not a single copy.

Like many humorists, Cranch was privately melancholic, and his depressive stints deepened as he aged. A posthumous tribute in Harper’s Magazine bluntly noted that Cranch was often silent and withdrawn. Certainly he had cause: the strain of his financial struggles, his artistic mediocrity, the fact that his father was mortified by his association with the Transcendentalists; the premature death of two sons.

Cranch himself, however, said the “blues” were simply part of his character, and always had been. For relief, he looked to music, and also to Emerson. Cranch could recite pages of Nature aloud; the book reliably lifted his spirits for four decades. Thirty-five years after the satirist and his subject went huckleberry picking together on Walden Pond, Cranch sent Emerson a new landscape painting to thank him for a lifetime of solace. “I owe you for all that your works have been to me.”

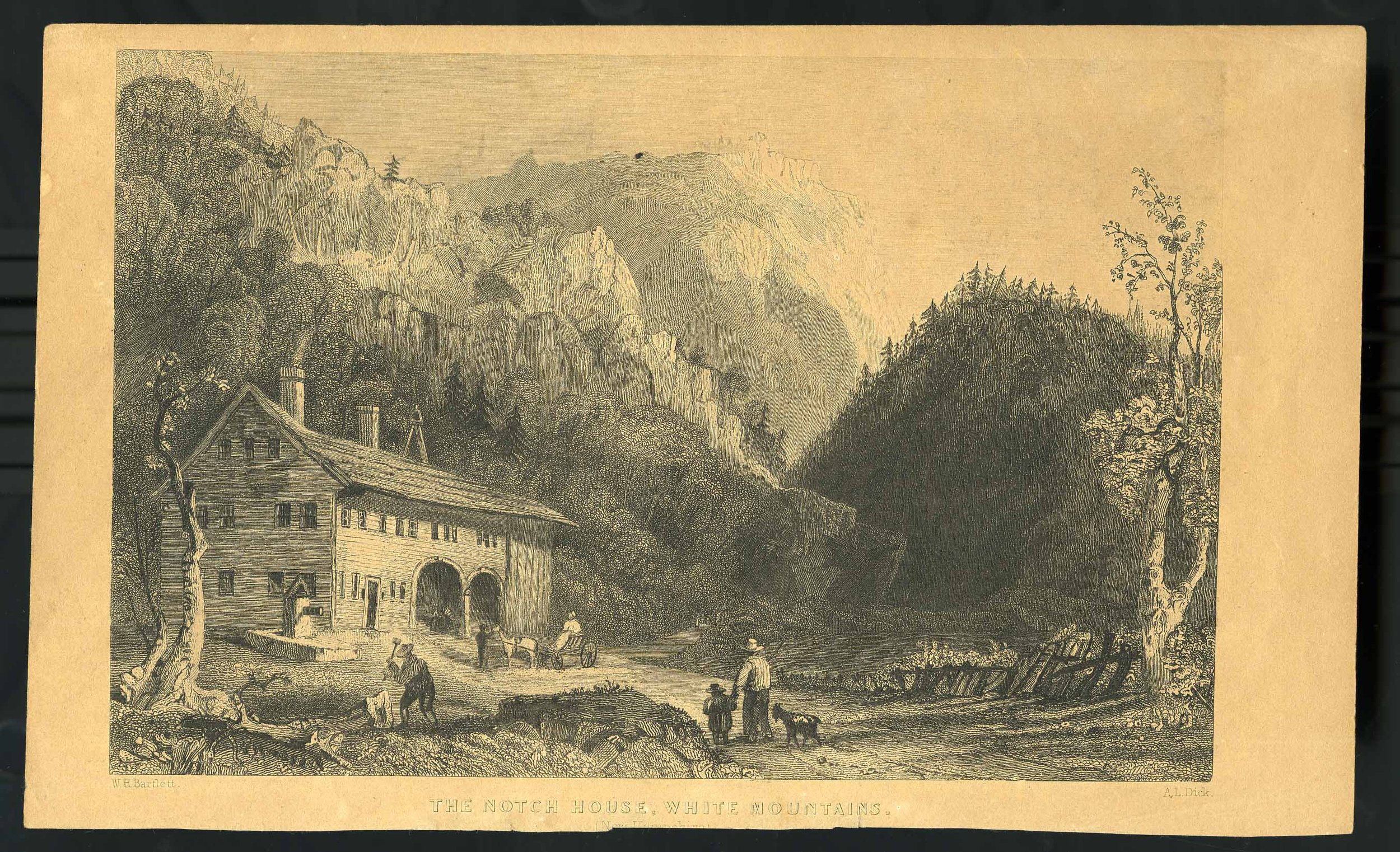

A. L. DICK AFTER WILLIAM HENRY BARTLETT, THE NOTCH HOUSE, WHITE MOUNTAINS, 1835-1850, LITHOGRAPH ON PAPER, MUSEUM OF THE WHITE MOUNTAINS, GIFT OF DAN NOEL, 2010.0001.1710

ETHAN ALLEN CRAWFORD’S RUSTIC INN, LOOKING SOUTH TO THE “GATE” OF THE NOTCH

MOUNT WASHINGTON IN THE DISTANCE, LOOKING EAST

Emerson’s Mountain Interval

It is well known that the untimely death of Emerson’s young first wife in 1831 from tuberculosis, and his own unease with church ritual led to his separation from the traditional ministry. But what do we make of the 1832 midsummer trip he took to the high mountains of New England between deep personal loss and the new calling he would soon pursue?

Twenty-nine-year-old Emerson’s career as a minister was already in decline. In late spring he had explained to his colleagues at Second Church of his terms for continuing as Associate Minister, terms they would eventually reject. He confided to his journal: “I have sometimes thought that, in order to be a good minister, it was necessary to leave the ministry” (Selected Journals, 193).

But first Emerson found it necessary to simply leave town, and retreated to his Aunt Mary Moody Emerson’s home in South Waterford, Maine. As Mary’s biographer Phyllis Cole noted, “He sought distance from the city—and also a kindred, if critical listener.” Then Emerson pressed west to Conway, New Hampshire, and up the Mount Washington Valley for a stay at Ethan Allen Crawford’s hostelry, at what was then called “the Gate of the White Mountains,” the spectacular pass known today as Crawford Notch.[1]

Mountains in myth are associated with divinity and the arts. In the classic tradition, Mount Olympus was the sacred dwelling of the gods, Mount Parnassus the home of the Muses, closely associated with poetry and the oracular. Emerson was also intrigued by the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth (1770-1850), who often invoked mountains in his nature-worshiping lyric poetry.[2] Philosophical, Wordsworth engaged in issues relating to individual spiritual experience within nature, as well as in organized religious community, as Emerson would—and before another year passed the two men would meet.

In his nature poetry, Wordsworth explored the heights and long views of mountain experience—the vast and infinite spaces in which humans may sense the divine, a presence engendering at once bliss and fear. The type of landscape that evokes this emotional response has long been called “sublime.” Decades later, Emerson would invoke this concept in the phrase “on the mountain-crest sublime” in his 1867 poem “Waldeinsamkeit” (Collected Poems, 189-91).

However familiar Emerson already was with hilltops in myth and poetry, it was likely his own Aunt Mary who planted the seed of her nephew’s first-hand mountain musings, the direct experience that is to nature writing what field notes are to a scientist. A pioneer in the Transcendentalist movement and an early influence on her brilliant nephew, she enjoyed breathtaking views of the northern Appalachians from her home in South Waterford, Maine. As early as 1823, Emerson wrote to a friend: “My aunt…has spent a great part of her life in the country, is an idolater of nature, and counts but a small number who merit the privilege of dwelling among the mountains…as the temple where God and the mind are to be studied and adored, and where the fiery soul can begin a premature communication with the other world” (qtd. in Cabot, v. 1, 96-97).

Three years later, Emerson was considering mountains as a place to reflect and a timeless source of wisdom, as he wrote to Aunt Mary: “I behold along the line men of reverend pretension, who have waited on mountains or slept in caverns to receive from unseen intelligence a chart of the unexplored country, a register of what is to come” (qtd. in Cabot, v. 1, 113).[3]

Most of all, perhaps, Emerson’s scenic retreat in 1832 ultimately provided solitude, and the calm, remote atmosphere he needed to make a pivotal decision. From Conway on July 6, he wrote: “Here, among the mountains, the pinions of thought should be strong, and one should see the errors of men from a calmer height of love & wisdom. … Religion in the mind is not credulity, & in the practice is not form. It is a life” (Selected Journals, 193-94).

Ensconced at the top of Crawford Notch on July 14, he wrote: “The good of going into the mountains is that life is reconsidered…and you have opportunity of viewing the town at such a distance as may afford you a just view nor can you have any such mistaken apprehension as might be expected from the place you occupy & the round of customs you run at home (Selected Journals, 194).

Still agonizing on the 15th, he wrote: “A few low mountains, a great many clouds always cover-ing the great peaks, a circle of woods to the horizon, a peacock on the fence or in the yard, & two travel-ers no better contented than myself in the plain parlor of this house make up the whole picture of this unsabbatized Sunday” (Selected Journals,195).

But later that same day, he seems to reach the decision he will live with—he concludes he cannot continue with “indifference & dislike” to a church practice others consider “the most sacred” (Selected Journals, 195). Back in Boston in September Emerson delivered his last sermon to his pastorate, ex-plaining his resignation. After touring Europe, he returned home in 1833 to begin his major career as a public lecturer and writer.

Mountains continued to occupy a place in Emerson’s imagination, itineraries, and poetry. In an unguarded 1841 journal entry, he recalled Aunt Mary, his brothers, and the mountains when he wrote: “…I would fain quit my present companions…& betake myself to some Thebais, some Mount Athos in the depths of New Hampshire or Maine, to bewail my innocency & to recover it, & with it the power to commune again with these sharers of a more sacred idea” (Selected Journals, 778).

He enjoyed a long stay in the Adirondacks with like-minded friends in the summer of 1858. With daughter Ellen, he climbed Vermont’s Mt. Mansfield in 1868 and returned to Crawford Notch in 1875, going further north to Bretton Woods. He visited Yosemite in 1871, at John Muir’s invitation. And of course, he had rambled in the Berkshires and knew Mount Monadnoc from family excursions.

Mountains are the subject of, or appear in many of Emerson’s poems including “Waldeinsam-keit,” “The Adirondacs,” “The World Soul,” and “May Day.” His 1847 poem “Monadnoc” is among those that express the intuitive communion he felt when alone in the presence of limitless nature to be found in the high hills. Consider this passage:

“On the summit as I stood,

O’er the wide floor of plain and flood

Seemed to me, the towering hill

Was not altogether still,

But a quiet sense conveyed;

If I err not, thus it said:—

‘Many feet in summer seek,

Betimes, my far-appearing peak;

In the dreaded winter time,

None save dappling shadows climb,

Under clouds, my lonely head,

Old as the sun, old almost as the shade.

And comest thou

To see strange forests and new snow,

And tread uplifted land?

And leavest thou thy lowland race,

Here amid clouds to stand?

And wouldst be my companion,

Where I gaze,

And shall gaze,

When forests fall, and man is gone,

Over tribes and over times,

At the burning Lyre,

Nearing me,

With its stars of northern fire,

In many a thousand years?’”

(Collected Poems, 159-62)

After Emerson, many came to the White Mountains. The area also inspired his peers James El-liott Cabot, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Sarah Orne Jewett, Thomas Starr King, Henry David Thoreau, and James Greenleaf Whittier. Much has changed since their time, but on a clear day Crawford Notch still affords spectacular views—and an otherworldly mood in autumn color, mist, twilight, or the fierce beauty of a storm in any season.

Today, the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Highland Center stands near the site of Ethan Craw-ford’s long-gone wayside inn. Last year some 14,000 guests stayed there, and countless others passed through as visitors seeking recreation, reflection, or renewal in the mountains.

1. We are indebted to Phyllis Cole’s excellent 1998 study, Mary Moody Emerson & The Origins of Transcendentalism, which gives a detailed record of Mary’s views of her nephew’s decision, his 1832 mountain interval, and cites his 1841 comparison of the White Mountains to the sacred hills of Greece.

2. As Marjorie Marjorie Nicolson noted in her landmark study of mountains in the history of Western thought, Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory, “There is no mountain mood or attitude we have found…that is not reflected in Wordsworth” (388). The epigraph is from Wordsworth’s 1814 poem “The Excursion.”

3. Emerson’s 1832 trip was not his first visit to the New Hampshire uplands. In August of 1829, he and his then fiancée Ellen Louisa Tucker visited Crawford Notch on a country vacation with hopes of improving her health. See “Meredith Village,” in Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks, Volume III, for his account of this tour.

Works Cited or Consulted

Cabot, James Elliot. A Memoir of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Volume 1. Boston/NY: Houghton/Riverside. 1895. Facsimile edition, nd.

Cole, Phyllis. Chapter 8, “God Within Us.” Mary Moody Emerson & The Origins of Transcendentalism. Oxford/NY: Oxford UP, 1998. 214-19.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Collected Poems & Translations. Harold Bloom and Paul Kane, eds. NY: Literary Classics of the United States. Library of America #70. 1994. 189-91. 49-60.

—-Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks, Volume 3: 1826-1832. “Meredith Village.” William H. Gil-man, Alfred R. Ferguson, eds. Cambridge/London: Harvard-Belknap/Oxford. 1963. 159-62.

—-Selected Journals, 1820-1842. Lawrence Rosenwald, ed. NY: Literary Classics of the United States. Library of America, #201. 2010.

Emerson, Ellen Tucker. Letters of Ellen Tucker Emerson. Edith E.W. Gregg, ed. Volume 2. Ohio: Kent State UP, 1982. 176-79.

Nicolson, Marjorie Hope. Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: the Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite. NY: Norton, 1963.

Wordsworth, William. “The Excursion.” The Complete Poetical Works of William Wordsworth. Student’s Cambridge Edition. Boston/NY: Houghton/Riverside, 1903. 403-524, lines 223-226.

— R. Davis, Ralph Waldo Emerson House

Ralph waldo emerson

Henry david thoreau

Emerson and Thoreau

Companions on a Journey of Self Discovery

In the early autumn of 1833, thirty-year-old Ralph Waldo Emerson was in Liverpool, England, about to return home to Massachusetts. He traveled to Europe, in part, to assuage the pain from the death of his first wife, Ellen. Her death prompted him to resign the ministry, and reconsider the whole of his life.

In the next two years (by 1835), Emerson successfully launched a second career as an essayist and public speaker, published his seminal work titled Nature, married his second wife, Lidian, and purchased the home on Cambridge Turnpike in Concord. He was on his way to becoming one of this country’s most notable, quotable and important thinkers. The literary movement in Concord at the time predominately centered around Emerson. He was at the epicenter of American thought.

Emerson’s choice to settle in Concord in the mid-1830s changed the life of a young student Henry David Thoreau, who was fourteen years younger than Emerson.

There were many similarities between Emerson and Thoreau. Starting with a strong affinity for the town of Concord. Emerson’s connections to Concord went all the way back to the town’s founding in 1635, when his ancestor Peter Bulkeley was among the early English settlers. Emerson’s grandparents lived in “The Old Manse” when the Revolutionary War began at the Old North Bridge. After he bought his house in 1835, Emerson lived in Concord for the rest of his life.

Thoreau was born in Concord and lived in the town for most of his life with his parents, brother and two sisters. He described Concord as “his Rome” and although he traveled widely in the northeast, he had no desire to live elsewhere.

The two men were bound by a strong belief in the importance of nature in developing creative and independent thinking. To share this message with others, they both chose writing and lecturing for their careers.

A Lifelong Friendship

Emerson and Thoreau met in the spring of 1837. Most likely Lucy Jackson Brown (Emerson’s sister-in-law) brought Thoreau to Emerson’s home and shared snippets of Thoreau’s poems. The year before they met, Emerson had published his essay Nature and Thoreau had borrowed it from the library and read it twice.

Emerson started keeping a journal while at Harvard and in October of 1837 Thoreau started his own after Emerson asked him “do you keep a journal?” Their journals became an integral part of their writings.

Two sturdy oaks I mean, which side by side

Withstand the winter’s storm,

And, spite of wind and tide,

Grow up the meadow’s pride,

For both are strong.

Above they barely touch, but, undermined

Down to their deepest source,

Admiring you shall find

Their roots are interwined

Insep’arble (qtd in Cramer, 121)

In April 1841, Emerson invited Thoreau to “live with me & work with me in the garden & teach me to graft apples.” (Walls, 120). Thoreau had free run of Emerson’s library, time to study, roam and write as he pleased.

In May 1841, Emerson wrote to Thomas Carlyle that in his dwelling lived “a poet you may one day be proud of: – a noble manly youth, full of melodies and inventions. We work together by day in my garden and I grow well and strong.” (120)

Both men found walking calming and introspective, whether alone or in company. While walking, Thoreau’s eyes would be focused on the ground looking for twigs, arrowheads, and flowers. Emerson would often face skyward as noted in his lecture series, The Conduct of Life, Behavior, “Love the day. Do not leave the sky out of your landscape.”

Thoreau lived with the Emersons until March 1843, when he left to go to Staten Island to tutor William Emerson’s children. Missing Concord, he returned in December.

In April 1847, Thoreau moved back and stayed with the family until Emerson returned from a European lecture tour in July 1848. Thoreau acted as head of a household that included, eight-year-old Ellen, six-year-old Edith, three-year-old Edward, Lidian, Lucy Jackson Brown and Emerson’s mother Ruth Haskins. Thoreau took care of the grounds, the kitchen garden and helped with financial decisions.

“The Country Knows Not Yet, or in the Least Part, How Great a Son it Has Lost”

Thoreau died on May 6, 1862 in Concord at only forty-four-years old. Bronson Alcott planned his funeral to be held at First Parish Church. The service was modeled after the memorial Thoreau had designed for abolitionist John Brown. It was a public event, a town ceremony.

Emerson wrote and delivered the eulogy at Thoreau’s funeral on May 9, 1862. Emerson’s closing remarks reflected his great respect for his friend and companion on the journey of self-discovery.

“The scale on which his studies proceeded was so large as to require longevity, and we were the less prepared for his sudden disappearance. The country knows not yet, or in the least part, how great a son it has lost. It seems an injury that he should leave in the midst his broken task, which none else can finish – a kind of indignity to so noble a soul, that it should depart out of Nature before yet he has been really shown to his peers for what he is. But he, at least, is content. His soul was made for the noblest society; he had in a short life exhausted the capabilities of this world; wherever there is knowledge, wherever there is virtue, wherever there is beauty, he will find a home.”

Works Cited:

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Thoreau.” The Atlantic Monthly, August 1862.

Cramer, Jeffrey S. Solid Seasons, Counterpoint Press, 2019.

Walls, Laura Dassow Henry David Thoreau A Life, The University of Chicago Press, 2017.

— R. Davis, B. Ewen, M. Purrington, Ralph Waldo Emerson House

The American Scholar

Emerson’s Call to Awaken American Thought

In late June 1837, Ralph Waldo Emerson was asked by the Harvard Phi Beta Kappa Society to address their annual meeting in August at the Battle Street Church in Cambridge. Emerson agreed and on August 31, 1837, he delivered “The American Scholar” to an impressive audience of theologians, writers, a Supreme Court Justice, and the president of Harvard. Emerson graduated from Harvard University in 1821.

Emerson utilized this opportunity to rail against the approaches to higher education, which were still focused on repetitive teachings of the past, reliant on European writers and artists, and increasingly leaning towards the importance of financial gain and material goods. Emerson declared, “The book, the college, the school of art, the institution of any kind…they look backward and not forward. But genius looks forward: the eyes of man are set in his forehead, not in his hindhead: man hopes: genius creates” (Emerson: Selected Essays, Lectures and Poems, 88). He encouraged Americans to recognize the new intellectual opportunities and to end reliance on other cultures. He prophesied, “Perhaps the time is already come…when the sluggard intellect of this continent will look from under its iron lids and fill the postponed expectation of the world with something better than the exertions of mechanical skill. Our day of dependence, our long apprenticeship to the learning of other lands, draws to a close” (83).

Emerson wrote “The American Scholar” at a time when America was becoming industrialized, causing the importance of the individual to be lost over the focus on the institution. Education was viewed as the path to wealth and position and not creative thinking and self-trust. He commented, “Colleges…can only highly serve us when they aim not to drill, but to create; when they gather from far every ray of various genius to their hospitable halls, and by the concentrated fires, set the hearts of their young on flame” (90).

Emerson stressed the importance of nature in developing creative and independent thinking. Original thought was natural and self-knowledge vital. He wrote, “The first in time and the first in importance of the influences upon the mind is that of nature…every day, the sun; and after sunset, Night and her stars. The scholar is he of all men whom this spectacle most engages” (85). He continued, “Its [nature’s] beauty is the beauty of his own mind. Its laws are the laws of his own mind. Nature then becomes to him the measure of his attainments…And, in fine, the ancient precept, ‘Know thyself,’ and the modern precept, ‘Study nature,’ become at last one maxim (86).

He concluded his address by urging his audience to consider thought revolution as naturally American, “…this confidence in the unsearched might of man belongs, by all motives, by all prophecy, by all preparation, to the American Scholar…thousands of young men as hopeful now crowding to the barriers for the career do not yet see, that if the single man plant himself indomitably on his instincts, and there abide, the huge world will come round to him” (101).

Emerson was experiencing significant change and taking on daring new opportunities in his own life, including challenging the American educational system and creation of ideas in “The American Scholar.” He had recently published his first important essay, Nature, in 1836, which was also the year his beloved brother Charles died and his son Waldo was born. Emerson had delivered “The American Scholar” at Henry David Thoreau’s graduation from Harvard (it is unclear if Thoreau was present) and subsequently they met.

On September 8, 1836, less than a month after the “American Scholar,” and the day before Nature was published, the Transcendental Club was formed by ministers, writers and educators who agreed with Emerson’s thoughts expressed in “The American Scholar.” The founding members (including Emerson) “found the present state of thought in America ‘very unsatisfactory’’ (Richardson, Emerson: The Mind on Fire, 245). Emerson was an active member of the Transcendental Club until it disbanded in 1844.

Amidst all of the life and cultural changes, Emerson was embarking on his remarkable 40 year career as an essayist, poet and speaker. Driven to share his thoughts publicly, his mind was racing with new ideas designed to increase individual expression and promote the importance of nature to thought and literature. As biographer Robert Richardson so aptly wrote, his was a Mind on Fire.

Although the reaction to “American Scholar” was somewhat mixed, Emerson published the talk at his own expense and all 500 copies were sold out within a month. Poet James Russell Lowell later reflected, “We were socially and intellectually moored to English thought till Emerson cut the cable and gave us a chance at the dangers and glories of blue water” (266). Oliver Wendell Holmes called The American Scholar, “our Intellectual Declaration of Independence” (263).

Works Cited:

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “The American Scholar,” Ralph Waldo Emerson: Selected Essays, Lectures, and Poems. Bantam Books, 1990, pp. 83-102.

Richardson, Robert D. Jr. Emerson: The Mind on Fire, University of California Press, 1995.

— B. Ewen, Ralph Waldo Emerson House

Photo by B. A. Economou

A Momentous Day: April 19, 1775

That day, full of fear and anticipation, hope and dread, leaving the past, with hearts, minds, bodies and a vision for a free future, is remembered with Ralph Waldo Emerson’s poem, “The Concord Hymn.”

Alerted by a single lit lantern at the Old North Church, riders including Paul Revere, Samuel Prescott, and William Dawes rode to warn the militia and Minutemen from local towns that the British army was on the move to Lexington and Concord seeking stores of arms.

Skirmishes along the way and the Battle at Lexington Green culminated in the Battle of the “Old North Bridge” in Concord, sending the British into retreat.

Emerson’s grandparents, the Reverend William Emerson and Phebe Bliss Emerson witnessed the struggle from their home, “The Old Manse,” located adjacent to the Old North Bridge.

Ralph Waldo Emerson was asked to compose a poem for the dedication of a commemorative monument on July 4, 1837. The white granite obelisk was erected on the east bank of the Concord River. The bridge had since fallen into disrepair and was no longer there.

The poem called “The Concord Hymn” was sung at the dedication to the tune of the “Old Hundred”. (Attributed to Louis Bourgeois,1551)

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood

And fired the shot heard round the world.

The foe long since in silence slept;

Alike the conqueror silent sleeps;

And Time the ruined bridge has swept

Down the dark stream which seaward creeps.

On this green bank, by this soft stream,

We set today a votive stone;

That memory May their deeds redeem,

When, like our sires, our sons are gone.

Spirit, that made those heroes dare

To die, and leave their children free,

Bid Time and Nature gently spare

The shaft we raise to them and thee.

Listen to the Concord Hymn performed by the Choir of the First Parish Church, Concord, Ma.

Emerson’s words resonate today as we remember, reflect, honor and express gratitude in this April, 248 years hence.

— I. Bornstein, Ralph Waldo Emerson House

Mary Moody emerson.

photo by B. ewen

Courtesy of Concord free public library

mary’s elm vale farm bordered bear pond in waterford maine.

mary moody emerson is buried in sleepy hollow cemetery in the emerson family plot. the inscription on her headstone was written by ralph waldo emerson. photo by b. ewen.

MARY MOODY EMERSON

A Powerful Influence on Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Aunt Mary Moody Emerson delivered “the most important part of Emerson’s education,” ultimately influencing his views, reading habits, and his writing. [1] Waldo [2] wrote “A good aunt is more to the young poet than a patron.” [3]

Her involvement in Waldo’s life commenced after his father William Emerson died in 1811 and Mary stepped in to help his widow Ruth raise her five sons. While Mary changed her living situation frequently, her influence was provided through thousands of letters and copies of her journal Almanack, started when she was 20 years old. Waldo began his own journal, The Wide World when he was 17 years old and a student at Harvard. She counseled all the Emerson boys to do what they were afraid to do.

Mary’s Almanacks and letters became a rich source of material for Waldo in his own writing, his poems, essays, and lectures. He kept four MME workbooks and often pleaded with Mary to send him sections of her Almanack, which he routinely copied and referred to as his career progressed from minister to author and speaker. After rereading Mary’s letters in 1841, he wrote, “Aunt Mary…is a genius always new, subtle, frolicsome, judicial, unpredictable.” [4]

Mary Moody Emerson was born in 1774 to William and Phebe Bliss Emerson; one of their five children, who also included Waldo’s father. Shortly after the American Revolution commenced beside the family home – Concord’s Old Manse – and with her father going to war as a military chaplain, two-year old Mary was sent to her grandmother in Malden, Massachusetts. (This was not an uncommon practice to share responsibility for children among family members).

Mary’s father, William, died in 1776 and even after her mother, Phebe, remarried Mary was not called back home. She often referred to this period as her “infant exile.” [5] Her grandmother also died when Mary was four years old and she was adopted by her Aunt Ruth Emerson. Mary’s childhood was characterized by drudgery and a lack of money and food.

Despite humble beginnings and very little access to formal education, Mary became a prolific (but largely unpublished) writer and a voracious reader of works by such authors as Milton, Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Plato, and Boston minister William Ellery Channing. She directed her nephew Waldo to read and appreciate these writers.

Mary decided at an early age not to marry (although she was asked). Fiercely independent, by the 1830s Mary championed causes of those oppressed, including antislavery movements and women’s rights to better education. She supported her nephew Charles as he gave an antislavery address in Concord in 1835, and attended several abolitionist gatherings. She counted intellectual and free-thinking women as her friends and confidantes, including educator Elizabeth Peabody, scholar Elizabeth Hoar, abolitionist Mary Merrick Brooks, scientist and educator Sarah Alden Bradford Ripley, and Waldo’s wife Lidian Emerson. Mary introduced Lidian to Mary Merrick Brooks, prompting Lidian to join Concord’s Female Antislavery Society.

Mary’s appreciation for nature and its impact on thought occurred much earlier than the mid-nineteenth century reflections that permeated essays, books, and talks written by Waldo, Thoreau and others. In the early 1800s, in the words of her biographer, “she lived and wrote a celebration of the solitary imagination and of nature as analogous to God, valuing both explicitly as a woman’s resources.” [6] In 1831, Mary purchased a farm in Waterford, Maine, which she named Elm Vale. She often wrote to her nephews to share her appreciation for the landscape surrounding Elm Vale, including the mountains, the trees and Bear Pond. Waldo, Ruth (Waldo’s mother), Charles and Lidian Emerson, Elizabeth Hoar, Sarah Alden Bradford Ripley, and Elizabeth Peabody, all visited Mary at “Elm Vale”. Mary sold Elm Vale in 1851, which was necessary but also very difficult for her. Before she left she wrote in her Almanack, “What a bird dancing on that graceful limb. Had I but his iron pen how could I give praise for every bird & tree w’h have met my responding senses in this tranquil and beautiful vale.” [7]

Energetic and very outspoken, Mary was often considered difficult and challenging. But those challenges were more than compensated with her commitment and support to the contemporaries and young people she valued. After meeting with Mary when she was 77 years old, Henry David Thoreau wrote, “it is perhaps her greatest praise and peculiarity that she, more surely than any other woman, gives her companion occasion to utter his best thought. In spite of her own biases, she can entertain a large thought with hospitality…In short, she is a genius…” [8]